me vs my data set.

it got hands.

Research is so messy. I feel like a kid in their room. More specifically, I feel like I’m sitting in my childhood room with blocks, Barbies, trucks, and other assortments of toys littering the floor. This is the most disorganized child I have ever taught. Ms Loveall said this to my mother in the first grade. It’s a sign of genius — you know, my mother quipped back.

I came into this program assuming that I could ride the dragon and find some kind of linearity. I could make the research easy. Yet, when you don’t know what you’re looking for, but you are indeed looking — the path is never clear. Instead, it takes you through mountains and valleys. My body violently responds to my research. I sweat. My hips get tense. The first year, I kept my yoga mat at the side of my desk. I used my Pomodoro timer to tell me when to stretch. The process hits me in my belly. My eyes bug out. My brow furrows. I lose track of space and time. I am a woman on a mission.

This past week, my data set opened up to me like a woman who has been pleading at the altar. For some reason, it made sense what data I needed to do my methodology. When you start doing critical work, they never tell you how to do it. The work to think across disciplines is exhausting. It is a work that I talk about often on here. The labor teaches you to walk slowly, take your time, smell the dusty books.

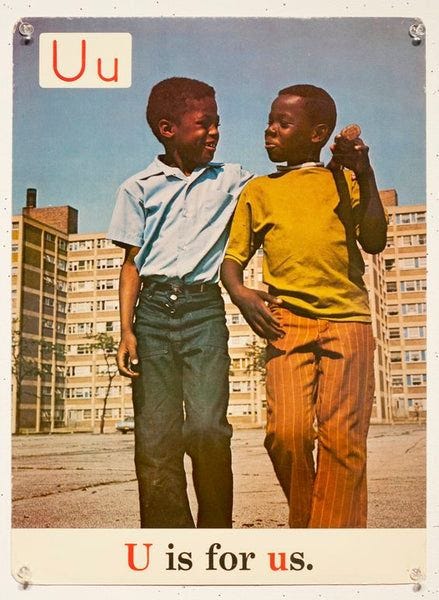

I am doing critical policy genealogy work. It is a method that analyzes how policies emerge, evolve, and functions as expression of material and social power over time. It brings together good ol’ Foucault with critical policy work to think through historical, discursive, and political conditions that shape what state activities are possible. In other words, I am thinking through how those things that govern us have ideas that are harmful to us. My particular interest is spatiality. Spatialized politics thinks about how political power operates through space. So, how space is designed, regulated, and contested as well as how they are lived and accessed. Here, space is constructed as social and political, material and symbolic.

Critical policy genealogy is a method for studying how policies come to be, with a focus on power, history, and the construction of knowledge. It asks: How have certain ideas, practices, and categories in policy become normalized or “taken for granted”—and at whose expense?

The challenge in this kind of work is understanding how much data do you need to see evolution over time and what kind of data you need to make a reasonable argument. It’s an interesting process cause on one hand, I am attempting to take anti-colonial, Black perspective to policy studies and on the other, I am attempting to critique how state language is intentionally de-spatialized. What does this mean? As a human being living on the Land, you are unable to critique something is intentionally universalized. The language provides no opening to think about how inequity of time, and space applies to different bodies. It’s a crystallized discourse rooted in a capitalist understanding of the human, place, and the threads between them.

Thinking through these ideas has me feeling all over the place with where I am going. Nothing feels out of my wheelhouse. In fact, I feel like I have been saying the above in one way or another for years. Yet, I struggled for language. I struggled a way to actually design social inquiry on new terms. The thing is, critical researchers talk about power, but don’t really talk about methods of interrogating it. They lean on old frameworks that they admit are insufficient without feeling the need to create new ones. They love to valourize “star” academics, without empowering students to get in the lab and do something that isn’t redundant or derivative.

I love to research and I love to teach. I am a writer and I am a creative. It has taken time to figure out who I am in the fray of an industry that cannibalizes itself and dissuades you from finding your own voice. I don’t see myself as an academic, nor do I wish to be one. I want to share knowledge and uplift voices of Black folks. I want to treat the work of Black thinkers with respect. I want to make knowledge more accessible for everyone. I want to democratize my work. I want to advocate for open source models. Perhaps this small break, this small realization of my data set… is a good sign of things to come.

Please let me know if you are also working through research design and wrestling data sets — academic, community based, for fun…. I’d like to know.

With love,

G.

So are you studying like Euclidean zoning, to redlining, to racial covenants, to gentrification?